Cruise ships range in size from a capacity of dozens of passengers, all the way up to well over six thousands people. That is the population of a small city.

All of those people have to live on a cruise ship for a few days, or even a week or longer. They expect nice conditions in well-kept staterooms where they take a shower and use a private toilet. These facilities use water, which may not seem like much individually, but it soon adds up.

So where does all that water go once it goes down the drain or toilet?

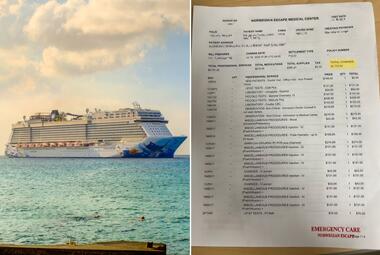

The average person will use 40 to 50 gallons of water per day, and if you multiply that by a few thousand people it soon adds up.

On a transatlantic sailing between Southampton and New York, even a small cruise ship would have produced almost 3000 tons of waste water.

Contrary to popular belief, ships don't just empty this waste water into the sea. The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) deals with marine pollution and restricts the discharges that ships are allowed to make.

Cruise ships collect all the waste in ballast tanks near the bottom of the ship.

In much the same way as you separate paper and metals and household recycling, cruise ships separate waste water onboard.

There are two categories of wastewater: gray water and black water.

The difference between the two is a bacteria that's present in each. Blackwater, which is waste from mainly toilets, has come into contact with solid waste and contains far more harmful components. Greywater, on the other hand, is things like waste water from showers and laundries. It's the sort of water that some environmentally friendly homes would collect and reuse, for example, when you're flushing toilets with old bath water and things like that.

Blackwater

So what do you do with blackwater once you start collecting it?

On land, it would go to a sewage treatment plants and actually on a ship, the exact same thing happens, albeit on a slightly smaller scale.

Down in the engine room, you'll actually find a full blown sewage treatment facility.

As sewage enters the system, it first passes through a filter to skim off anything particularly large.

From there, it passes into the next chamber, the aeration chamber. Aerobic means the bacteria needs oxygen to be able to survive.

If we were to just dump all the sewage in here, the bacteria would soon use up their oxygen. So ships actually use air blowers to give the bacteria a constant supply of oxygen and the sewage as a food source. This is essentially just an accelerated form of decomposition.

These bacteria are all alive, which is why ships are so careful with the chemicals they use in their toilets. The last thing they want is to go and kill all these helpful bacteria accidentally.

Once the bacteria do their job, we move to the next stage, which is the settlement chamber. Similar to how a drink left out too long may start separating into layers, heavy materials will sink to the bottom and the water floats to the top.

The dense stuff can actually be sent back to the earlier chamber for the bacteria to do more work on and it some point it becomes so dense that it gets caught in the filters and then it can be removed and either sent for incineration or disposed off on shore.

The fluid stuff at the top, which by this stage is practically just water, then gets cycled into the final treatment chamber.

This final treatment is just sterilization, which could be chlorination, like we use in a swimming pool, or it could be another high tech method like UV treatment. Basically, we're just making sure that the last of the harmful bacteria is gone.

Finally, we're left with a result that's water that's perfectly safe. It's actually safer than some drinking water, but not to worry, no one actually drinks it.

This water is sent to another storage tank where it can wait until the ship is in a geographical area where it's allowed to discharge.

What started out as the most harmful blackwater actually enters the sea as the cleanest, practically fresh water.

Greywater

Unlike blackwater, greywater doesn't actually need to pass through the sewage treatment plant at all.

Some ships will process greywater along with the black, but not always.

One issue with combining the two is it is difficult to control the chemicals people use in showers and sinks, and that shampoo could kill all off the helpful bacteria in the treatment of blackwater.

Of course, simple filtration is used to remove anything large that shouldn't be in the greywater. Treatment of greywater is usually minimal, and most ships will simply discharge it when they're far enough away from land.

There are a growing number of geographical areas that do prohibit, or at least limit, greywater discharge. One particular area of note is Alaska, where there have been a few high profile prosecutions for breaching their limits.